The Engine Under the Hood

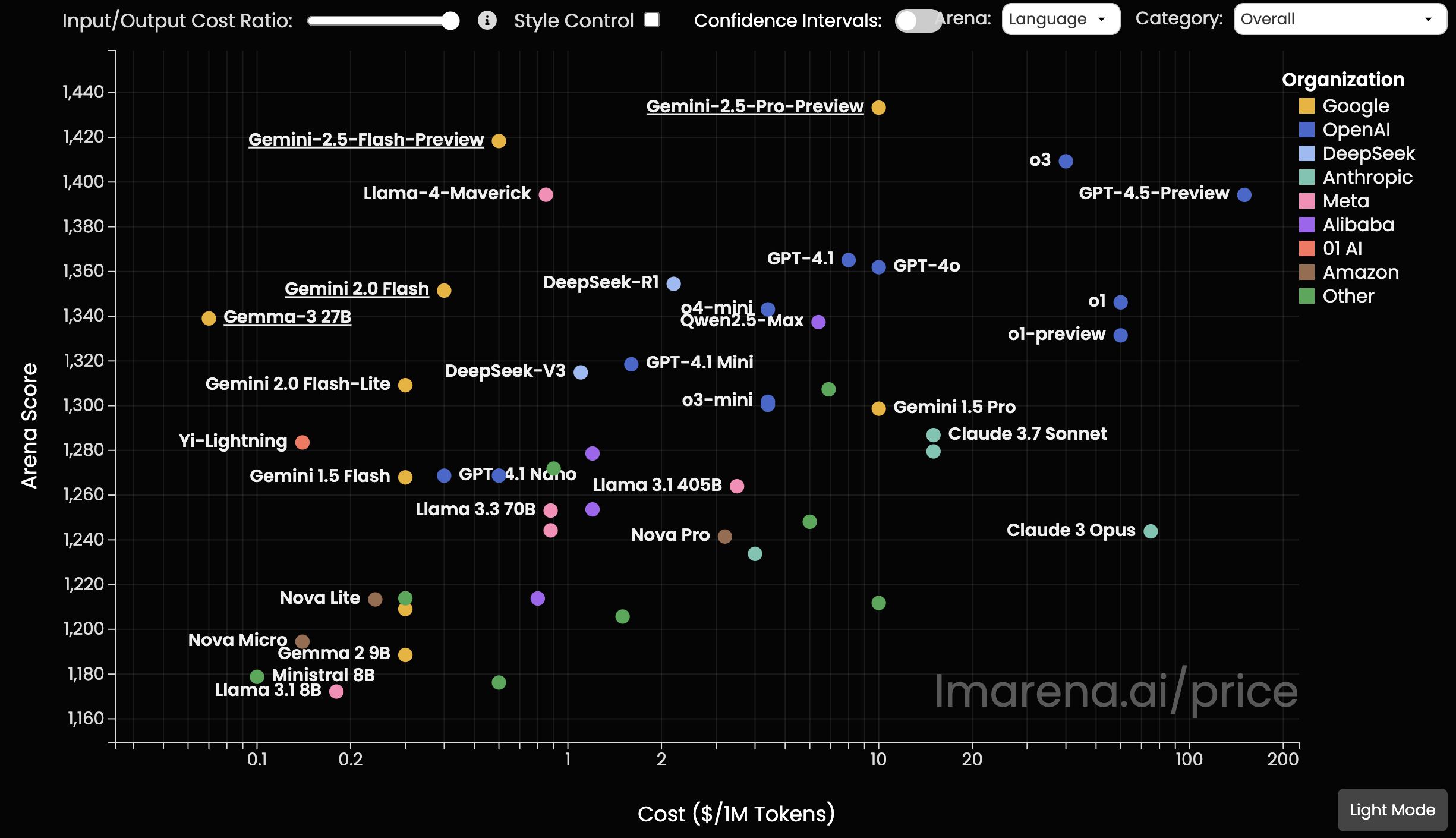

If you’ve looked at the price-performance charts for large language models recently, you might have noticed something strange. Google, the company many had written off as being on its back foot in the AI race, is quietly dominating the corner that matters most: the one for models that are both very good and very cheap.

A Clear Lead in Performance-for-Value

This dominance isn’t just theoretical; it’s visible in plain sight on leaderboards like the LMSYS Chatbot Arena, which pits models against each other in blind tests. Across the entire spectrum, Google’s Gemini family is establishing an undeniable pattern. Whether it’s the small and versatile Gemma, lightning fast and inexpensive Gemini Flash, or the top-tier and powerful Gemini Pro, each model consistently delivers performance that punches far above its price point. This isn’t just winning one category; it’s a strategic placement across all tiers, offering remarkable performance for value no matter the use case.

This consistent lead begs the question: how are they doing it? This isn’t a temporary sale or a minor lead. It’s a structural advantage. The answer has less to do with the models themselves and more to do with the custom engines they run on.

The NVIDIA Tax and the TPU Gambit

For most companies, the AI boom comes with a hefty tax. It’s paid to NVIDIA. To build or run any serious AI at scale, you need to buy or rent their GPUs, and you pay the price for their market dominance. This isn’t a criticism of NVIDIA; they make exceptional hardware. It’s just a statement of fact about the economics of the industry.

Google decided to play a different game. Over a decade ago, they started building their own chips: the Tensor Processing Units (TPUs). This is fundamentally an argument about vertical integration, which is not dissimilar to how Apple sees its Hardware and Software going hand-in-hand. Instead of renting a factory, they built their own. But more importantly, they got to design every machine inside it.

A GPU is a powerful, general-purpose engine. We use it for graphics, scientific computing, or AI. A TPU is different. It’s a custom-built engine designed for exactly one purpose: running neural networks. At their core, neural networks process information by performing a staggering number of matrix multiplications. Data is represented in large, multi-dimensional arrays in the form of “tensors,” and training or running a model is essentially a marathon of multiplying these tensors together. A TPU strips away unnecessary components and perfects this one operation. Its architecture, built around a dedicated Matrix Multiply Unit (MXU), is like a hyper-efficient assembly line designed for this single mathematical task. It’s less like a car engine that can do anything and more like a Formula 1 engine designed for pure, unadulterated speed on a specific track.

This specialization goes even deeper. Modern AI often deals with “sparse” tensors. Imagine looking up a single user’s viewing history from the billions of hours on YouTube. The resulting data tensor would be enormous, but nearly every value in it would be zero, representing a video the user hasn’t watched. A general-purpose chip wastes immense effort and energy multiplying by zero over and over again, which is a computationally useless task. Google’s TPUs have specialized hardware called SparseCores that are built to handle this exact problem. They are engineered to identify and skip these zero-value entries, only performing calculations on the meaningful, non-zero data. This isn’t a theoretical edge; it’s what makes products like Google Search and Ads run efficiently at planetary scale.

When you see the results of this strategy, like the prices for Gemini, you’re not seeing a marketing gimmick. You’re seeing the economic output of a more efficient machine. Google can afford to charge less because it costs them less to get the answer. And this advantage is compounding. Their newer TPU generations, Trillium and Ironwood, show an obsessive focus on widening this lead by dramatically increasing memory and improving an already specialized architecture. They aren’t just getting faster; they’re getting more efficient at the exact workloads that are becoming AI’s biggest bottlenecks.

So while we obsess over which chatbot is more clever, the real moat in AI may be forming at a much deeper level. It might not be the model’s intelligence, which can be fleeting, but the brutal economics of running it at scale. Other companies are in a race where the cost of fuel is set by a single supplier. Google is quietly showing everyone what happens when you own the oil refinery.